The Lie of the Land:

Truths about Landscape and Food Learnt through Art

Philippa Clarke

“Farming looks easy when your plough is a

pencil and you’re a thousand miles from the cornfield” (Dwight D. Eisenhower)

This essay examines instances where art and agriculture come together. The analysis is situated in the context of agricultural history in order to question our relationship with the way food is produced. It focuses on particular artworks: Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews,

Mishka Henner’s Feedlots and Goldin+Senneby’s Not Approved and Shifting Ground to demonstrate significant changes in the way land is managed, as seen from the vantage-point of art criticism.

The artworks are geographically varying in nature but the focus of the essay is British agriculture. The essay concludes by reflecting on the direction needed to be taken by contemporary artists inspired by the land.

Art is insight. It contains hard facts: structure, composition, motifs etc. but it also contains subtler layers derived from reading it within a wider context. As Catherine M. Soussloff puts it, when writing about painting and the philosopher Michel Foucault, it is “a form of disclosure, it refers to and includes institutions, systems of belief and subjects that come into contact with it though interpretative and viewing situations”. (Soussloff, 2017) Both Foucault and Soussloff go beyond thinking of a painting as a historical object and are interested in the potential of art to transform by exposing mechanisms of social constructions. Foucault writes about the transformative

power of his writing on his own being. Soussloff is also interested in the transformations that occur when we critically interpret paintings, transformations that can be used to inform our actions in the world.

I’m interested in harnessing that transformative power through looking at art and through my own artistic practice of painting and drawing. Through art I wish to explore our relationship with the land to inform my mark-making. I am interested in how the

countryside has been shaped and continues to be shaped by those who own it, work it, live in it and encounter it. This is important at a time when nature’s ecosystems are being devastated by modern farming methods and three quarters of

the world’s land-based environment have been “significantly altered” by human actions (IPBES, May 2019). How we use

land has never been more crucial. Looking at the intersection between art and agriculture I wish to consider how art can prompt questions about the way we farm and produce our food.

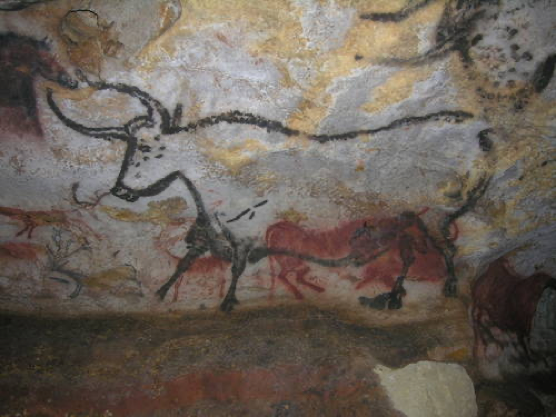

From the earliest times art has depicted food production methods. Paleolithic cave paintings show the food stuffs of a

hunter-gathering society. Ancient Egyptian burial chambers were adorned with images of oxen-drawn ploughs, hoes, rakes and irrigation technology.

![Figure 1. Lascaux cave painting, photograph Bandarin, F. (2006)]()

From a dense forest of possibility, I have

chosen three artworks at the intersection of art and agriculture.

The

first artwork to consider is Mr and Mrs

Andrews by Thomas Gainsborough: a double portrait conversation piece of

Robert Andrews of Aubreries and Frances Carter. The painting is believed to

have been commissioned to celebrate the Andrews’ wedding in Sudbury, Suffolk (Hayes 1980).

![Figure 2. Thomas Gainsborough - Mr and Mrs Andrews (xxxx)]()

Mr

and Mrs Andrews has been

the subject of much critical attention. What interests me is what it tells us

about agricultural development and the emergence of agrarian capitalism. Agricultural historian, Mark Overton,

considers the 18th and early 19th centuries as “a crucial

period of agricultural advance in England worthy of the description

agricultural revolution.” (Overton 1996).

I shall consider Mr and Mrs

Andrews in the light of the agricultural innovations described by Overton.

Painted in 1748, Mr and Mrs Andrews is at the cusp of the agricultural revolution. In the 100 years following there will be a

population explosion as agricultural innovations keep pace with tripling people

numbers. Unusually for a portrait, the subjects are not in the centre of

the canvas. Instead Mr Andrews stands by his seated wife on one side of the

canvas whilst a sweeping expanse of landscape is given equal weight on the

other.

Mr Andrews stands proud: the estate manager

overseeing a thriving agricultural operation. An operation designed to maximise

yield. All around are visual clues to allow us to read the painting as a social

document.

The fields of green are likely to be clover.

The Norfolk four-course system of crop rotation developed in the next-door

county has been up and running for a couple of decades. The system promoted by

former Secretary of State, Charles, 2nd Viscount Townshend aka Turnip Townshend

rotates wheat, turnips, barley and nitrogen-fixing clover in a four-year cycle. Cereal yields are significantly

improved in nitrogenous soils. It is a sustainable way of improving

productivity.

Wheat has been planted instead of a

lower-yielding more traditional grain such as rye, and permanent pasture has

been turned over to arable. To offset the loss of permanent pasture, the sheep

we see grazing would have been fed fodder crops such as turnips, another new

agri-innovation.

It is possible that the sheep could have

been selectively bred. We know that another East Anglian, Thomas Coke of

Holkham was pioneering selective breeding by crossing the slow-maturing Norfolk

Horn with the English Leicester, a breed that thrived on turnip fodder. Between

1806 and 1807 Thomas Weaver of Shrewsbury was engaged by Coke to paint

portraits for Coke and his tenants. A large conversation piece, Thomas

Coke and his Southdown Sheep, shows Coke making notes about his Southdowns - a breed know for “easy lambing, docility and ease of finishing” (Southdown Sheep Society, 2019).

![Figure 3. Thomas Coke and his Southdown Sheep (1807) by Thomas Weaver of Shrewsbury]()

The estate is

used for shooting. Traditionally birds were hunted by hawk or by netting

or shooting on the ground but during the 18th Century what was known as

“shooting flying” became popular amongst the landed gentry with the improvement

of shotgun technology (Chester,

1933). To me, a country girl, the unpainted area in the lap of Mrs Andrews is definitely the beginnings of a pheasant, although critics

have speculated otherwise. Mr Andrews

sports a fine shotgun with his bags of shot

draped from his belt. A loyal gun dog looks up admiringly at his master

reinforcing the idea of master and

loyal servant.

As landowner and proprietor of a shoot Mr

Andrews flexes the muscles of power. Power to manage landscape, power to

control who should be on his land, power to have someone condemned to death.

The penalties for poaching at this time were extreme. The “Black Act” was

passed in 1723 making poaching with a blackened face a hangable offence. A farm

worker could not supplement his meals with a rabbit or bird without risk of

imprisonment or worse.

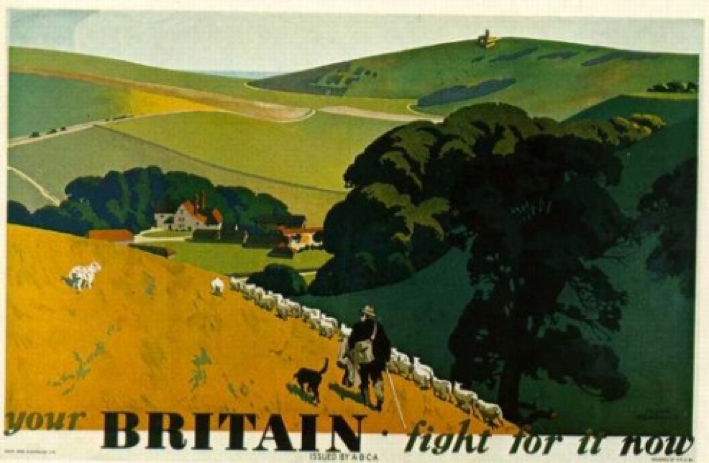

The landscape of Mr and Mrs Andrews reinforces an idea of England as “green and

pleasant land”. An enduring image both pastoral and picturesque. Celebrating

man’s dominium over nature through ripe harvest and well-fed livestock and

presenting the charming qualities of natural woodland. The imagery is one of

control and order. It is the same imagery that we see in Frank Newbould’s World

War 2 propaganda posters. It is a landscape that is worth fighting for.

![Figure 4. Poster for War Office 'The South Downs’ Your Britain Fight for it now by Frank Newbould (1942). Imperial War Museum]()

It is also worth noting that at the start of World War II the government took control of British farming. Needing to maximise production (food rationing continued until 1953) the Labour government guaranteed prices with the 1947 Agriculture

Act. In his award-winning book, The Killing of the Countryside, Graham Harvey describes 1947 as the beginning of the “industrialization of Britain’s countryside.” (Harvey 1997).

Returning to Mr and Mrs Andrews, despite the bucolic imagery and sustainable model of farming there is a “dark side” to the landscape, a term that was coined by John Barrell when writing about the poor in English painting (Barrell 1980). This is because farming is no longer about subsistence. It has become about business. From this point onwards we will see a quest for productivity that

will change the landscape forever. Pesticides, fertiliser, antibiotics and farming on an industrial scale. The stage has been set for environmental catastrophe.

![Mishka Henner - Feedlots]()

In this section I shall use the artwork of Mishka Henner to think about farming and food production and just as I

did with the Gainsborough, I will go beyond the aesthetic to learn more.

Philosopher John Benson, when looking at aesthetic and non-aesthetic reasons for valuing landscape, maintains that whilst it is possible to look at a landscape in terms of broadly sensory concepts: forms, colours, textures, sounds etc that this mode of perception is highly artificial. The aesthetic of the landscape cannot be separated from its function. As soon as we separate the aesthetic from the practical we are seeing it “one-eyed”. He compares it to a game of football: “An analogy would

be looking at a football match simply as a temporally extended pattern of swiftly evolving spatial configurations, in abstraction from its being a contest between two sets of more or less skillful human players, the spatial configurations being the result of the players’ attempt to score. The act of abstraction may be worth doing from time to time to heighten awareness of one aesthetic element in the total experience. But it is the total experience that matters.” (Benson

2008).

It’s easy to be beguiled by the painterly quality and abstracted imagery of Mishka Henner’s large archival pigment prints Feedlots, made in 2012 and 2013. But associations with abstract expressionism or the sublime become eradicated by a stomach-turning realisation of horror that they are not about expressive marks or the wonder of nature. The patterns, shapes

and colours have tricked us. Rather than giving us Benson’s “total experience” in one go, Mishka Henner has cleverly used the heightened aesthetic of abstraction to amplify the moment when one realises what the imagery actually is.

![Figure 5. Centerfire Feedyard, Ulysses, Kansas photograph by Mishka Henner (2012-13)]()

Figure 6. Coronado Feeders, Dalhart, Texas(detail) photograph by Mishka Henner (2012-13)

What we see is colossal examples of the immense extent of man’s exploitation of the natural environment and of living

creatures. Rather than standing before this imagery as Edmund Burke might have us trembling in awe of the sublimity nature we stand with disbelief; shame-faced and disgusted.

Henner’s photographs show CAFOs: Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations which are used as rapid fattening units to allow a

cow to reach a weight ready for slaughter in just 18 months. By contrast a Welsh beef farmer friend from my agricultural student days confirmed that it should take between 24 and 30 months to rear grass-fed prime beef. The feedlot cattle are fed a diet of grain and protein supplemented with hormones to achieve such rapid weight gain. The images show thousands of cattle and

chemical lagoons used for treating the millions of litres of manure.

Just as photographer Andreas Gursky casts a critical eye over capitalism and globalism playing with the scale of landscape

and humanity, Henner’s Feedlotsshines a light on the epic proportions of US industrial farming. Industrial farming that has grown from the early days of agrarian capitalism that took

root in Gainsborough’s time.

There are in the region of 700 feed lots in the US, each holding as many as 100,000 cattle.

In the UK the definition of a CAFO is a unit with “at least 125,000 broilers (chickens raised for meat) or 82,000 layers (hens which produce eggs) or pullets (chickens used for breeding), or 2,500 pigs, 700 dairy cattle or 1,000

beef cattle.” (Davies and Wasley 2017).

Henner’s satellite images taken from space seem to underscore how distanced we have become from the way our food is

produced. It feels as if we need to go from this bird’s eye view to have a look up close. We need to reacquaint ourselves with what food really is and where it has come from. “There’s a huge difference between my Welsh Blacks and those animals in a USA feedlot” says my Welsh farming friend.

Of course big does not necessarily mean bad: arguably there are animal welfare advantages through increased monitoring and

access to veterinary care but Henner’s photographs show the cramped conditions of the CAFOs and vast toxic lagoons chemically processing manure. And what the imagery doesn’t show is the cataclysmic amounts of methane, a major greenhouse

gas, being produced by these operations. There is no doubt that this sort of industrial farming is harmful to the environment through methane emissions, toxic run-off and destruction of bio-diversity.

Unlike Gursky who photographs his own imagery, Henner is interested in making images when conventional aerial or

drone photography is not permitted. He makes use of publicly available

satellite images and his subject matter includes military outposts and

oilfields where photography is forbidden. In fact it was through searching for

images of oil fields on Google Earth that he came across the feed lots.

Taking unauthorized images of farms is

prevented in many US states by so-called “ag-gag” laws. Henner’s Feed Lots acted

as catalyst for investigative journalist Will Potter to scrutinize these ag-gag

laws which he describes as “an explicit attempt to outlaw undercover

investigations and whistle blowing if they negatively portray the industry”. Despite this, Henner does not see himself as

an activist. In an interview for ARTnews he says “If I was an activist, I don’t

think I would be putting art on a gallery wall.” (Greenberger 2015).

Perhaps Henner would see himself more as

part of a tradition of photographers who catalogue industry. The consistent way he makes images of the

farms from the same height and in same format calls to mind Bernd and Hilla,

the tutors of Gursky, who photographed industrial structures such as water

towers and gas works in sets and grid formations. One also thinks of the images of British

photographer John Davies whose black and white photographs of the British

landscape juxtaposes the Turner-esque qualities of vast space and nature with

the productive activities of mining and industry.

In Henner’s work the distance the images are

taken from is not only for aesthetic effect.

It is analogous with how distanced we are from food production. Not only have we become disconnected from how

things are grown, we have an expectation that we can eat cheap meat every day

as a right. But factory farming is not just problematic for meat consumers.

Industrially grown soya, maize and grains

require high levels of fertilisers, fungicides and pesticides. Soils that are

intensively ploughed and chemically treated become almost biologically dead.

And meanwhile our desire for cheap

foodstuffs continues unabated. Most of us do not make the connection between

what we put in our mouths and the environmental cost of producing it. The

Brazilian Amazon burns as more and more forest is cleared for cattle rearing

and the mega-farms continue to prosper.

Although at present the British system of

farming is primarily grass-based with an average herd size of 135 cattle

(National Beef Association 2019) recent research by the Guardian and the Bureau

of Investigative Journalism showed 12 industrial fattening units in the UK

where herds of up to 3000 cattle are kept in grassless enclosures. This is a

worrying trend.

Not Approved and Shifting Ground by Goldin+Senneby

In this next section I will continue to

think about our relationship with the aesthetics of landscape and will use

artwork by Swedish art collaboration Goldin+Senneby to do so.

Animal welfare and environmental concerns

are not a new phenomenon. A 2003 reform to the EU Common Agricultural Policy

decoupled subsidies from particular crops and introduced “single farm payments”

that were subject to environmental and animal welfare cross-compliance

conditions.

Goldin+Senneby brought this to our attention

in their 2009 work Not Approved. This

was part of their year-long enquiry into agricultural policies. Not Approved consisted of 32 photographs

taken by Swedish bureaucrats in 2003 that showed landscapes that had not

received agricultural funding because they did not meet the EU aesthetic criteria.

![]()

![]()

![Figure 7. Images from Not Approved by Goldin+Senneby (2009)]()

![]()

The so-called field inspection photographs

are nondescript and bland. The landscape is scruffy. Captions by the

photographs give some insight as to why the land was rejected: “Not approved,

completely overgrown”, “Not pollarded”, “Solitary oak trees, front tree not

approved”.

That there should be a defined aesthetic for

landscape is an interesting concept. How is this decided? John Benson, when

writing about the English landscape says that it is “to a greater or lesser

extent artefactual” (Benson, J 2008). Most landscape is not designed for

aesthetic contemplation and has instead been shaped by man. He cites the

parklands of English country houses as exceptions which can be considered as

“large scale artworks”.

Goldin+Senneby were interested in the shift

between farmer as land worker and farmer as artist. In Shifting Ground (2008), a scripted speech commissioned by

Goldin+Senneby, the artist, played by an actor, describes a visit to his

father’s farm. His father can no longer afford to keep cows. Only the biggest

farms with 200 or more cows can survive. The artist’s father feels despondent

as he can no longer take pride in his milking herd. His way of life has been

lost. He still maintains his pasture, ploughing and making hay in order to

qualify for the twice yearly subsidy describing it as “pasture polishing”. That

the farmer receives public funding for creating an aesthetic with the landscape

is interesting to Goldin+Senneby. It is similar to the artist receiving arts

council funding. In the work the artist has a heated discussion with the

playwright who has scripted the speech. The script writer accuses the artist of

ignoring the biggest issue: that of receiving public funding. The artist

declares his vested interest as a recipient of public money and refuses to

discuss it further.

Going back to the 2003 EU agricultural

policy, it seems that environmental concerns were not really at the heart it.

Rather, it was about preserving a picturesque view of the landscape where the

practical use has become obsolete. A sentimental idea of idyllic rural life.

Neat, tidy, well-tended and controlled. Just

as it has been since Gainsborough’s time.

In a 2018 interview with Goldin+Senneby,

William Kherbek picks up on their depictions of labour as a means of

aestheticizing value creation. Kherbek

sees this coming from an art-historic tradition (Kherbek 2018) and there is no

doubt that the working classes have long been used in artworks for purposes both

aesthetic and political. Goldin+Senneby

imbue a feeling of sympathy with the farmer and a sense of absurdity and

frustration about the state of agricultural politics.

In both Not

Approved and Shifting Ground the

farmer has been put in the position of an artist maintaining an aesthetic with

the landscape. Unlike Benson’s country house analogy, the farmer did not design

the original landscape with an aesthetic intent. Perhaps it would be more

appropriate to call the farmer a conservator of a museum of the past.

Preserving the image of well-tended

agricultural landscape can be problematic. We know that rewilding programmes

have been enormously successful at re-establishing plant, animal and insect

life but these initiatives are frequently hampered by complaints that the

landscape looks uncared for. Where ragwort and docks thrive so do insects but

these plants are traditionally seen as examples of poor pasture and bad

management. In her smash-hit book Wilding, Isabella Tree describes onerous

battles with members of the public who thoroughly objected to the re-wilding of

their 1400 hectare estate in Sussex finding it disorderly and untidy (Tree

2018).

It is difficult for people to separate the

idea of landscape from its purpose. An untidy landscape means unreliable farm

management. We urgently need to rethink what the purpose of landscape is and

what it looks like. The catastrophic decline in biodiversity is reason enough.

The practical use of landscape should be to provide an environment where

species can flourish. With this will come a new aesthetic where the look of

landscape is not separated from its purpose.

A

new way of seeing

Art can play a vital role both in

reinforcing a new landscape aesthetic and helping us make a connection about

where our food comes from. Cultural factors including art contain the

transformative powers that Foucault spoke of that can influence our behaviours,

our lifestyle choices and values.

During Gainsborough’s time there is no doubt

that the average person would have had a connection with where his or her food

came from. They weren’t distanced from the killing of animals for meat or the

cultivation of land. Even the gentry who had servants and staff to prepare food

would have been familiar with 17th Century Dutch still life paintings depicting

game and fish.

Today, images of food production are harder

to come by. Mishka Henner’s work highlights the extreme disconnect that we have

with food production. On the other hand Goldin+Senneby shows that environmental

issues have been taken into consideration but only in as much as they reinforce

the idea of idyllic countryside. Intensive farming continues and is big

business.

And let us return to Foucault. In Foucault’s

Art of Seeing by John Rajchman we learn how Foucault used

before-and-after-pictures to make things visible. These pictures were not just of what things

looked like, they were “how things were made visible, how things were given to

be seen, how things were “shown” to knowledge and power.” (Rajchman 1988). A

second feature of Foucault’s before-and-after pictures proposed a

“philosophical exercise in seeing”. Having seen the before and after, what is depicted is shown in a new light or in

a different way.

In all three artworks we see control of the

landscape by the wealthy and powerful, whether it be the gentry in the

Gainsborough, the government in Goldin+Senneby’s

work or corporations controlling Henner’s feedlots and the governments who put

in place laws that prevent us from seeing them.

In the latter two works, the artists have gone beyond documentary-making

to harness the power of aesthetics to highlight our distance from food

production (Henner) and to create a sense of the absurdity of present-day

agricultural policy (Goldin+Senneby).

The environmental emergency is a call to

arms for artists and art curators to challenge the status quo and visually

represent a new alternative for food production and landscape management. By

making things visible we put pressure on policy makers and have some influence

on people’s behaviours.

Conceptual artists such as Henner and

Goldin+Senneby have been able to record, document and critique landscape

through photography, performance and other interventions. The challenge for

contemporary painters is huge as they have to draw attention to environmental

concerns without being overly didactic or illustrative. Environmentalism is a growing force across

popular culture and the arts, whether it be rewilding plot lines in The Archers

or the current Eco-Visionaries exhibition at the Royal Academy.

There are little green shoots of optimism.

The Government’s new Agriculture Bill had its first reading in parliament on 16

January 2020. The Bill provides the legal framework for the way farmers will

receive financial assistance once the UK leaves the EU when farmers will no

longer receive EU subsidies. At the

heart of the bill is a requirement for the government to “take regard to the need to encourage the production of food

by producers in England and its production by them in an environmentally

sustainable way.” (Parliament, House of Commons 2020). Farmers will receive payments for restoring

and enhancing both land and water and for supporting the public in gaining a

better understanding of the environment.

It strikes me that artists can play a huge rule in supporting this

public understanding. The role played by

artists in revolution is well documented and this new agricultural revolution should

be no different.

References

Adelaide, University of (5th July 2019) ‘Study shows potential for reduced methane from cows’ Phys.org.

https://phys.org/news/2019-07-potential-methane-cows.html

Barrell, J. (1980) Dark Side of the Landscape. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Benson, J. (2008) ‘Aesthetic

and Other Values in the Rural Landscape’. Environmental

Values 17, no. 2, pp 221-38. www.jstor.org/stable/30302639

Becker, C. ‘How art became a force at Davos’ World Economic Forum (26 Feb 2019) https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/02/how-art-became-a-force-at-davos/

Chesney, R. and Shirely, R. (2018) Rethinking Landscape, White Chapel Gallery

https://soundcloud.com/whitechapel-gallery/rethinking-landscape-rebecca-chesney-rosemary-shirley

Dalton, J (2 March 2019) ‘Drone footage shows spread and size of Britain’s mega-farms that ‘speed up climate change’’ independent.co.uk https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/farm-climate-change-animals-drone-footage-video- a8804661.html

D’Aurizio, M. (11 January 2016) ‘The Gesture that Makes the Mark’ Flash Art https://flash---art.com/article/the-gesture-that-makes-the-mark/

Daswani, N. (10 January 2017) ‘From Dada to Davos, How artists speak truth to power’ World Economic Forum

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/01/from-dada-to-davos-how-art-speaks-truth-to-power/

Davies, M. and Wasley, A. (2017) ‘Intensive

farming in the UK, by numbers’ The Bureau

of Investigative Journalism

https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2017-07-17/intensive-numbers-of-intensive-farming

Fox, C. (August 4 2018) ‘Agri-culture: the artists drawing inspiration from farming’ Independent.ie

https://www.independent.ie/business/farming/rural-life/agriculture-the-artists-drawing-inspiration-from- farming-37168622.html

Food Climate Research Network.

https://fcrn.org.uk

Greenberger, A. (21 October 2015) ‘The Man

Who Laughed at Surveillance Technology: Mishka Henner on His Jarring Images

About Images’, ARTnews

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/the-man-who-laughed-at-surveillance-technology-mishka-henner-on-his-jarring-images-about-images-5016/

Harvey, G. (1997) The Killing of the Countryside. Vintage

Hayes, J. (1980) Thomas Gainsborough. Tate Gallery Publications Department p20

Heinecke, Andreas (23 July 2019) ‘Why we need artists who strive for social change’ World Economic Forum

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/07/why-we-need-artists-social-change/

Hoskins, W.G. (2013) The Making of the English Landscape. Little Toller Books

IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy

Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Service) (2019) - Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on

biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy

Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

https://ipbes.net/global-assessment-report-biodiversity-ecosystem-services

James, S. (15 June 2013) ‘Reviews/Mishka Henner’ Frieze

https://frieze.com/article/mishka-henner

Janick, J. (2002)Ancient Egyptian Agriculture and the Origins of Horticulture. Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA.

https://hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/pdfs/actahort582-2002.pdf

Jeffrey, S. (26 June 2003) The EU common agricultural policy, The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/jun/26/eu.politics1

Jones, J. (28 Jun 2001) ‘This land is our land’ The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2001/jun/28/artsfeatures.arts

Kherbek, W. (29 May 2018) ‘Goldin+Senneby / An

Interview’ Samizdat Online

http://www.samizdatonline.ro/goldin-senneby-interview-nome-gallery/

Kirby,

Chester (1933) The English Game Law System, The

American Historical Review. Vol. 38, No. 2 pp. 240-262 Oxford University

Press on behalf of the American Historical Association. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1838294

Mallon C on behalf of the National Beef Association (26 November 2019) ‘Letter of complaint to BBC following unclear message in global beef production documentary’,

National Beef Association Website

https://www.nationalbeefassociation.com/news/11937/letter-of-complaint-to-bbc-following-unclear-message-in-global-beef-production-documentary/

Mishka Henner website. https://mishkahenner.com/Feedlots

Mitchell W.J.T. (1994) Imperial Landscape - Landscape and Power. The University of Chicago Press Ltd, London. Republished 2002

Overton,

M. (1996) Agricultural Revolution in

England: The Transformation of the Agrarian Economy 1500–1850. Cambridge

University Press

Parliament, House of Commons (2018). ‘Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations Private Members’ Bills – in the House of Commons at 10:12 pm on 12th November 2018’.They Work For You

https://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=2018-11-12d.149.6

Parliament, House of Commons (2019-20) Agriculture Bill Bill 007 2019-20 https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/58-01/0007/20007.pdf

Rajchman,

J. Foucault’s Art of Seeing. October,

vol.44, 1988, pp. 89-117.

www.jstor.org/stable/778976

Soussloff, C.M. (2017) Foucault on Painting. University of Minnesota Press

Soil Association (2018) ‘To plough or not to plough - Tillage and soil carbon sequestration’ The Soil Association Website Policy briefing

https://www.soilassociation.org/media/17472/to-plough-or-not-to-plough-policy-briefing.pdf

Souter, A. (29 March 2019) ‘Creative approaches to rewilding’, The Ecologist

https://theecologist.org/2019/mar/29/creative-approaches-rewilding

Steinhauer, J. (7 December 2012) ‘Using Art to Describe Labor’, Hyperallergic https://hyperallergic.com/61501/using-art-to-describe-labor/

South Downs Sheep Society

http://www.southdownsheepsociety.co.uk/about-1

Thomas Weaver of Shrewsbury - Animal Artist of the Agricultural Revolution

https://www.thomasweaverofshrewsbury.com/paintings.html

Travers, J. ‘When farming and art intersect, the world is treated to magnificent masterpieces’ Lost at E Minor, (17th February 2016)

https://www.lostateminor.com/2016/02/07/farming-art-intersect-world-treated-magnificent-masterpieces/

Tree, I. (2018) Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm. London: Picador

Whitechapel Gallery, The Rural: Contemporary Art and Spaces of Connection

https://www.whitechapelgallery.org/learn/the-rural/

Images

Figure

1. Lascaux cave. Photograph by Bandarin,

F. (2006) photograph. UNESCO

Permanent

URL: whc.unesco.org/en/documents/108435

Figure

2. Mr and Mrs Andrews by Gainsborough, T. (1748) National Gallery

Mr and Mrs Andrews https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/thomas-gainsborough-mr-and-mrs-andrews

Figure 3. Thomas Coke and his

Southdown Sheep painting

by Thomas Weaver of Shrewsbury. (1807)

https://www.thomasweaverofshrewsbury.com

Figure 4. Poster for War Office 'The

South Downs’ Your Britain Fight for it now by Newbould, F. (1942). Imperial War Museum

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/20289

Figure 5. Centerfire

Feedyard, Ulysses, Kansas image

by Mishka Henner (2012-13)

https://mishkahenner.com/Feedlots

Figure

6. Coronado Feeders, Dalhart, Texas(detail) image by Mishka Henner (2012-13) https://mishkahenner.com/Feedlots

Figure

7. Images from Not Approved by

Goldin+Senneby (2009) https://goldinsenneby.com/practice/not-approve